HIV is not a death sentence. As our first week of presentations roll to a close, the classrooms and village halls we conduct them in erupt into a chorus of chanting as our audience echoes back this statement, again and again, growing louder and more affirmed in their belief in this reality.

In a country devastated by the effects of HIV, we aim to shine a light on the people living with the disease and encourage them that life does not end with their diagnoses.

Following our last presentation in Chizungu, I was introduced to a man that had already been living by this mantra. Felix Marda was diagnosed with HIV in 2011. Following his admittance to hospital with tuberculosis, he discovered that his condition had come as a by-product of HIV.

At first, Felix says he struggled to understand the condition and felt that the end of his life was imminent, but with the support of his family, he came to accept his status and encouraged others to do the same. His employer swiftly let him go due to 'fears for his health', despite Felix feeling well enough to continue after receiving counselling and ARV treatment, and within four months his friends had abandoned him for fears of being associate with an openly HIV+ person.

Unemployed and fearful of the attitude towards HIV in his community, Felix established the Tamanyachi Health Centre in order to tackle the stigma towards HIV and educated those living with the condition on the best ways to cope. As the stigma towards the condition is much more focused on women than men, Felix has encouraged more women to work as peer educators for his organisation. On the gender bias, Felix states, "we are all one people, we have a common bond". However, it is evident that gender inequality for those living with HIV is still rife within the community.

On the other side of the room, I was then introduced to Fadress Nkhata, a woman living with HIV who has already encountered her fair share of gender-based discrimination. She faced public humiliation following the divorce from her first husband as he refused to allow her to seek treatment for her condition. After remarrying in 2005 her new husband also denied her this right, tearing up the health passport that allows her to receive life prolonging medicine. Fadress decided to go it alone and seek treatment, despite fears of abuse and further stigmatisation at the hands of her husband and peers alike. Three months later, her husband had died from AIDS, having never sought medical treatment.

Today, Fadress is feeling strong and living a happy life with her daughter who is also HIV positive. She has overcome the discrimination she faced to become an active and popular member of the community. Despite her successes however, she still feels that discrimination is rampant towards woman living with HIV. "We are still oppressed. For many women, they fear disclosing their condition as they will no doubt be persecuted by men. For men, HIV is just a slowdown, because they are dominant. For women, the effects are much worse".

Fadress says the only way to resolve this oppression is to fight back and for women to assert themselves as strong and independent in the face of neglect and gender prejudice.

As more education is provided and more people openly disclose their status, both Felix and Fadress are confident that equality is on the horizon. However, with neglectful cultural practises still ongoing and men still openly discriminating against women living with the condition, I can only hope they are right.

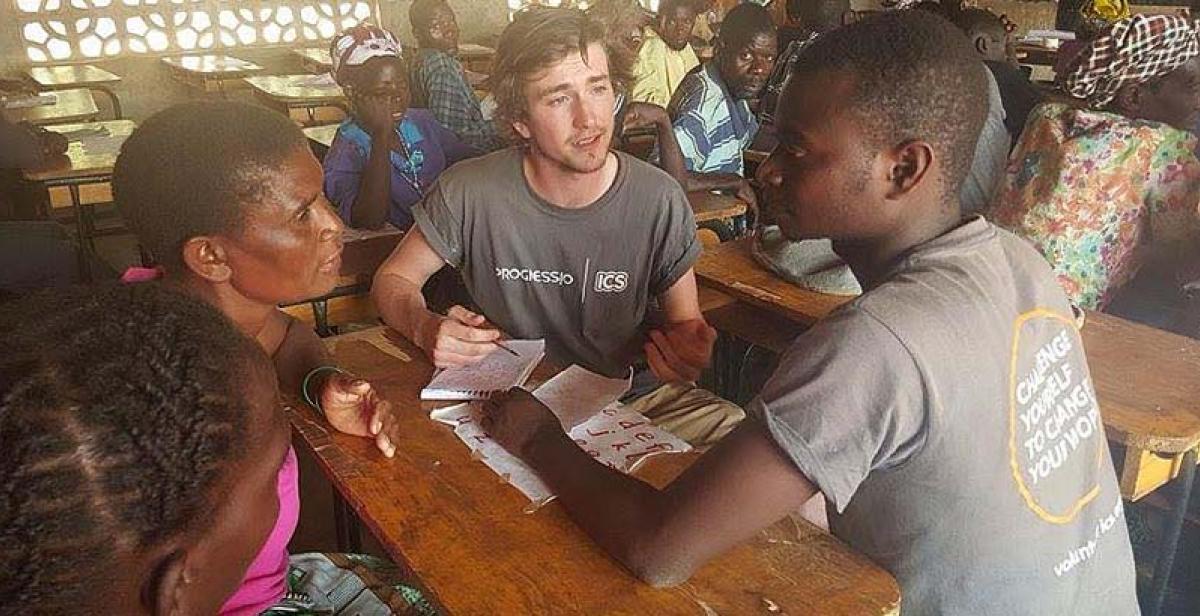

Written by ICS volunteer Lewis Begbie