Driven by excitement and with a keen interest in politics, I spent some time researching the political and economic profile of Malawi before starting my ICS adventure. The overall picture I got was of a country which had had more than its fair share of poverty and economic problems, with a recent World Bank study ranking Malawi as the poorest country in the world. On the other hand, Malawi has also enjoyed absolute peace since its independence 1964 and its nascent democracy sees little sign of faltering. Yet the experience of living in Nkhata Bay for the past two months has given me a much more informed and realistic picture of the challenges facing my host-country.

Since first stepping foot in Malawi, I have found a country that is still reeling from the effects of the political scandal known as Cashgate. This describes a series of events from September 2014 onwards that lifted the lid on endemic corruption at the heart of Capitol Hill. Investigations into the shooting of the Finance Ministry’s Budget Director and the discovery of USD$300,000 in the boot of a civil servant’s car, found that Malawi had lost millions of dollars to corruption, through a loophole in the financial management system. Although it remains unclear which ministers were involved, an independent report by accountancy firm, Baker Tilly, estimates that a total of USD$32m had been defrauded in just six months.

In response there have been a number of arrests and Joyce Banda’s People’s Party was ousted in the 2015 elections and replaced by the incumbent Peter Mutharika’s Democratic Progressive Party. Yet the repercussions of Cashgate go far beyond this. At the time, 40% of Malawi’s budget came from the direct aid of Western donors. Once the news of this scandal broke, there was a unanimous decision among the donor countries to stop all direct aid to Malawi, although it is worth mentioning that DFID continues to support Malawi through indirect aid (see: https://devtracker.dfid.gov.uk/countries/MW/projects). The effects of this go without saying, with a budget deficit and medicine shortages in the hospitals among the problems associated with the donor’s withdrawal.

What is believed and has been widely reported in Malawian media, is that a condition for the reintroduction of direct aid are a number of controversial social reforms. Not a day goes by without the mentioning of the legalisation of homosexuality debate in the country’s #1 newspaper, The National. In a God-fearing country, there has been a predictably strong backlash to this suspected donor-demand. The most pious claim that they would rather starve than see homosexuality decriminalised.

One country that attaches no such demands to its direct aid, is China. As part of an USD$80 million loan, Malawi has built a new road from Karonga to Chitipa, the Malawi University of Science and Technology and a shiny new parliament building in Lilongwe. With more Chinese assistance inevitable, it is not difficult to imagine Malawi’s allegiances shifting further to the East. An emergency donation of maize, amounting to K6.5bn has even been made to alleviate the hunger that this country is currently experiencing.

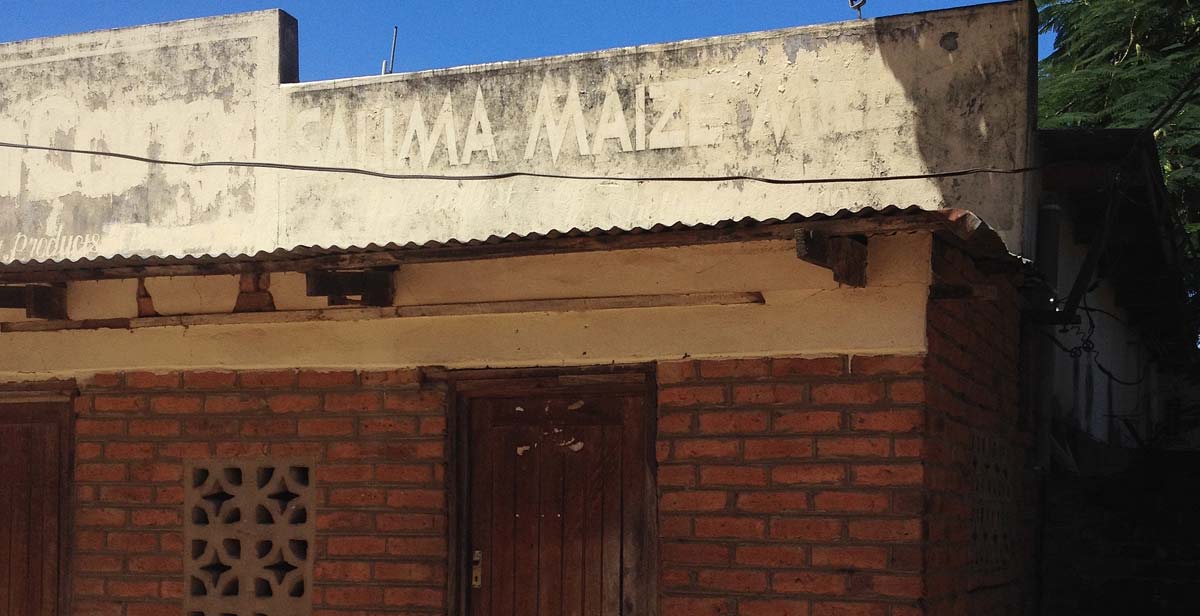

This leads onto yet another big challenge that my host-country is currently facing - climate change. In a country of subsistence farmers, a majority of the population relies on maize. This crop is ground into flower, then mixed with water to make the national staple food nsima. However, the 2015 harvest was far from favorable. This was largely due to far too much rain from November-March, with large swathes of the South of Malawi experiencing flooding. In comparison this year, although months to go until the harvest, there has been nowhere near enough rain with the maize harvest unlikely to be anywhere approaching sufficient. The Chinese donation will help, but hunger appears to be the most likely outcome and the queues outside the local ADMARC building (where Malawians purchase maize and fertilizer at subsidized prices) are appearing to get longer and longer here in Nkhata Bay.

The pain felt here is further exacerbated by the lack of depth and diversity to the Malawian economy. The only real cash-crop is tobacco and although there are rumors of oil beneath Lake Malawi, the risk of an oil slick is surely too great for a country where more than 1/5 rely on fish as their main source of protein, not to mention the tension in Tanzania - Malawi relations on this issue. There has even been a recent debate surrounding the potential economic benefits of legalising chamba (Indian hemp).

The combined effects of Cashgate, aid-withdrawal, climate change and reliance on tobacco have seriously weakened the Malawian economy. As soon as I stepped off the plane at Lilongwe airport, had my passport stamped and made my way to the Exchange Bureau, I found that I would not receive 325 Kwacha that my guidebook (printed in 2012) said I would, but 950 Kwacha. Inflation has continued at a staggering pace throughout my placement, with the exchange rate now 1050 Kwacha for every British pound. People here really feel the squeeze felt from inflation, with wages rarely rising in line with inflation unlike the stipends that the volunteers receive from Progressio every two weeks.

A radio announcement comes on the morning radio show ‘Sunrise Malawi’ telling citizens not to worry about inflation and to trust the government’s economic policies that have been put in place to straighten things up. Announcements like this may increase the people’s hope for a stronger economy, yet the plethora of problems that I have set out here are surely too much for one government alone.

Although the problems facing Malawi show little sign of receding, there is a category whereby the country is exceptional by regional and even global standards. Since 1964 Malawi has enjoyed peace. It is the only African country never to have gone to war at home or abroad. There is little to no ill-feeling among Malawi’s various tribes - my host father’s wife is Tumbuka whilst he is Lomwe, which is incredibly common. I am yet to feel threatened so far in my ICS placement and there are no signs to suggest that organised crime exists.

Although initially skeptical of the oft-coined title ‘The Warm Heart of Africa’, experiences from the last month and a half indicate that this country almost certainly qualifies for this. The hordes of smiling children that seem to appear everywhere to the car mechanics that I chat to everyday on my way to work leave me utterly convinced of this.

My host father summarises the current feeling here perfectly. Whilst the cost of maize rises while the value of the Kwacha falls, he and his family can walk freely without the fear of violence or crime. There is peace and normality here and this must surely count for something.

Written by ICS volunteer Jack Davis