It was a tired, grubby, but nonetheless excited group that finally alighted from the second leg of our gruelling 14 hour airborne journey from Heathrow, onto sizzling, sunburnt tarmac. Initial impressions of the country that was to be our home for the next 10 weeks were difficult to discern, as airports the world over are pretty much of a muchness at first glance, but we soon got our first taste of the labyrinthine, Kafkaesque Zimbabwean bureaucracy as the stern-faced immigration officials at first refused to let us through, due to some sleep-deprived confusion on our part over addresses and the completion of various forms required in order for us to officially and legitimately set foot in the country. However, thanks to a timely intervention from Mark, Progressio’s Programme Officer in Zimbabwe who was at the airport to greet us, we were eventually permitted to pass and stepped blinking and yawning into the soft air and sultry sunshine of Harare.

Peering eagerly out of the windows of our ‘kombi’ (a quintessentially Zimbabwean mode of transport with which we were very quickly to become intimately acquainted with), we drank in the sights and sounds of a new and unfamiliar city. Despite its British colonial background, Harare is laid out on an American-style grid pattern with a sharp distinction between the sprawling, quaintly ramshackle bungalows of the suburbs and downtown’s bland, functional skyscrapers interspersed with imposing, monolithic official and government buildings bearing the Orwellian nomenclature of Zimbabwe’s myriad state Ministries. As we threaded our way through clouds of choking traffic fumes, horns beeped, music blared, buses swerved, and pedestrians dodged recklessly between onrushing vehicles and the many potholes littering the crumbling, careworn asphalt streets and pavements. Punctuating the prevailing dusty browns, drab greys and faded greens that dominated the city’s colour scheme were welcome flashes of cool lilac, vibrant orange and vivid red provided by the jacaranda trees lining the avenues; the brightly coloured attire of Harare’s rather snappily dressed inhabitants; and numerous billboards gaudily promoting life’s essentials – especially the ubiquitous red and white of Coca Cola, predictably enough.

Upon arrival at the River of Life training camp, which was to be our base for the next 8 days of in-country orientation and training, we were made to feel incredibly welcome by the staff there – a first taste of the traditional Zimbabwean hospitality which we would experience much more of in the days to come, and was, if anything, even more pronounced once we’d made the long drive to Binga where we will be for the next 8 weeks. It was immediately noticeable that nearly everywhere we went or whoever we talked to, we would be greeted by warm, friendly smiles, elaborate handshakes and a general openness and willingness to engage in amiable conversation whatever the situation or time of day. Nobody we met was ever too busy to say hello, which was a refreshing change from the heads-down, no eye contact rushing around of the UK with its dead-eyed, zombified commuters, to which we were accustomed.

Once the national volunteers had arrived in Harare (the cohort of 13 internationals from the UK is joined by an equivalent number of Zimbabwean volunteers from within the communities in which we’d be working, then split into 3 working groups each attached to a different partner organisation), then the training could begin in earnest. First on the agenda was a brief cultural overview of the areas in which we’d be working. Binga district is located in the Matabeleland North province in the west of Zimbabwe, along the shores of Lake Kariba (the second largest man-made lake in Africa) on the border with Zambia. The area is demographically distinct from the rest of Zimbabwe, being home to the Tonga people, who are culturally, linguistically and geographically apart from the mainstream Shona ethnic group who dominate the country’s politics, with the result that the area is somewhat ignored and underdeveloped by the central government. This was followed by a crash course in the Tonga language, delivered by Josias, a jovial and thorough teacher who retained his broad smile and good humour even as he patiently answered our barrage of questions about the bewildering variety of ways to say ‘there’ in Tonga.

Next up was a presentation from the organisation we’d be working with upon our arrival in Binga: Ntengwe for Community Development. Founded in 1999 by Elizabeth Markham after she realised that the only charitable group working in the district was Save the Children, Ntengwe aims to facilitate the development of a ‘well-informed, empowered and responsive community able to deal with HIV/AIDS.’ We learnt that the majority of our work would be focussed on HIV/AIDS and the issues surrounding it, and in conjunction with Ntengwe’s focus on developing the community’s response to it from bottom-up rather than projects imposed from above, that this would involve advocacy, education and awareness raising and an emphasis on working with local youth as well as supporting those living with the virus. Although we’d all assiduously researched the organisation before we’d even arrived in Zimbabwe, it was exciting to learn specifically what we’d be helping to achieve during our placements and how the organisation works, as well as meeting some of the staff who we’d be working alongside. We then hurried off to draw up a provisional programme of projects we wanted to implement as well as pre-existing ones we felt we could contribute to during our placements, brimming with ideas and enthusiasm, before presenting it to the other two groups.

Then before we knew it, Friday rolled around and it was time to finally leave for Binga. Packed on to a dilapidated but, mercifully given the 800km journey to come, well ventilated bus the 18 of us struck out on to the long, long drive across Zimbabwe from the high veld of Harare to the sweltering, subtropical climes of the Zambezi valley. Soon after passing through Gokwe, a small, isolated town strangely reminiscent of the frontier towns of the Wild West, only built from concrete rather than wood and appearing abruptly out of the parched desolation of the bush, the tarred road finally gave out just as the sun went down. After already being on the road for 8 long, sweaty hours, patience within the increasingly fractious group was beginning to wear thin, compounded by the interminable jolting of the dirt road and the so-called DJ’s insistence on playing the same 3 Zimbabwean pop songs at ear-splitting volume over the bus’s ancient and heavily-distorting speaker system. Some however, myself included, preferred to emphasise the ‘romance’ of the journey, seeing it as adding to the authenticity of our fledgling Zimbabwean adventure. Eventually, some 13 and a half hours after leaving Harare, we wearily stepped into the thick, insect-filled Binga night and made straight for our mosquito net-guarded beds to recuperate and prepare for the exciting, but slightly daunting prospect of the hard but no-doubt rewarding work that was to come.

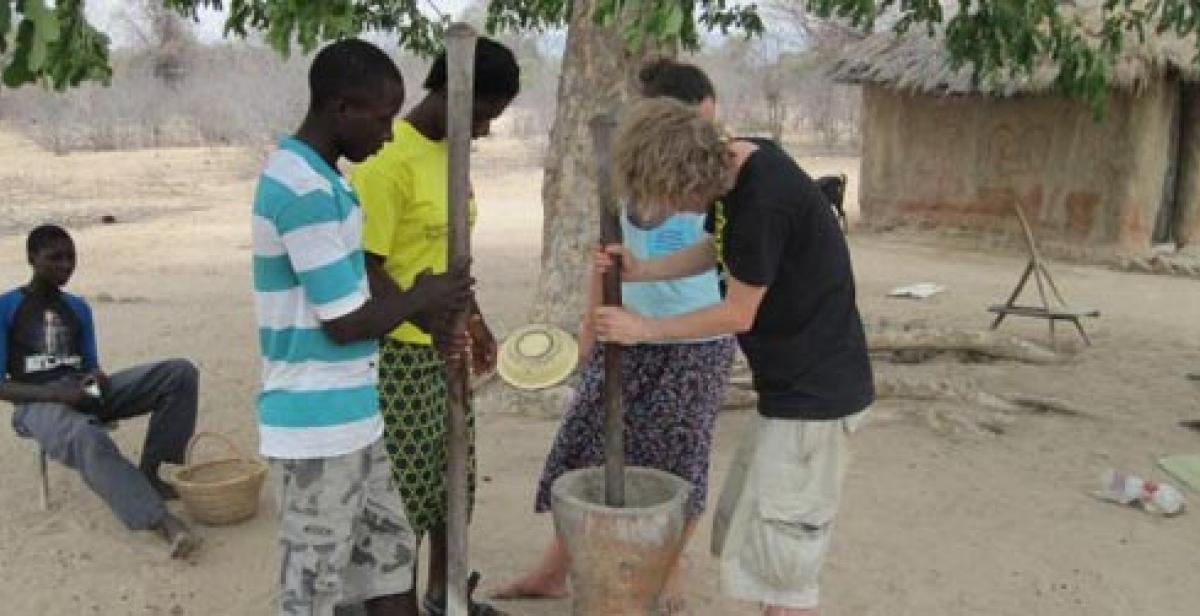

Progressio ICS volunteer Dan Broughton in Zimbabwe

Dan's group are also on twitter, follow them @ICSTeam_Ntengwe

Comments

Outstanding piece of writing-

Outstanding piece of writing- I really enjoyed reading it. Congratulations, and hope Dan continues his fascinating blog.